4:11:22

“What you want is fame?

Then note the price:

All claim

To honor you must sacrifice.”

“Admonition,” Nietzsche, The Gay Science

“Woe unto them that call evil good, and good evil; that put darkness for light, and light for darkness; that put bitter for sweet, and sweet for bitter!”

-Isaiah, 5:20

I have been thinking a lot about Stanley Kubrick’s 1999 film, Eyes Wide Shut, which I first saw in 2001. I rented it at a local video store and watched it at home. I was a young graduate student living alone in a room in West London. I didn't understand what it is was. I did not see it as real, nor the out-of-touch "dream" many critics wrote it off as. No one asked what kind of dream it was or what the dream was really about. The dream was a cover. But the cover was not a dream. The film’s famously "intimate" sex scenes (no one but Nicole Kidman, Tom Cruise, and Stanley Kubrick were allowed on set during filming) between the then married Kidman and Cruise, who play the married Bill Harford and Alice Harford, are just the opposite. They are as public, performative, ritualistic, and sacrificial as the freemasons’ (the film does not identify them as that) Satanic orgies at Somerton, a place not unlike The Overlook (the phrase eyes wide shut, a mafia term, echoes the name overlook, which represents not only what is hidden, but what is deliberately repressed and unheeded. It also refers to the blindfolds and masks; literal covers. Piano player Nick Nightingale tells Bill Hardford: “I play blindfolded.”) in its ties with evil and the occult. Both Kidman and Cruise, Bill and Alice, are a couple being watched. They are also actors being watched, but in a way that is different from how we normally watch actors in a movie. How we had historically watched them up until that point—1999. This was something more, something different. Actors hide behind their characters. They hide behind the camera. Actors are voyeuristic objects, but so are films, as Kubrick reminds us. Everyone is misled.

The premise of this “special” viewing was that Kidman and Cruise knew they were going to be watched as a real-life power couple pretending to be a fictitious power couple, and what would that double act look like? What would it reveal about their real-life marriage, which seemed to also be a fiction. This performance required being alone in a room with a director for days at a time for the sole purpose of shooting these risqué scenes that are less about married intimacy, sex, or desire, and more about the conspiratorial crisis of social reality and the real power it hides. Depending on how you look at it, actors are part of this hidden crisis because they are never what they seem. They present and portray a world that cannot be trusted, or fully grasped, but is advertised as upstanding, enviable, glamorous. They also present a version of power that is not true. A power that covers a real power we never see. In his 2000 essay about Eyes Wide Shut, “Introducing Sociology: A Review of Eyes Wide Shut,” Tim Kreider writes: “It shows us that these people are empty and amoral…ultimately more concerned with social transgressions like infidelity than with crimes like murder—just as the film’s audience is more interested in the sex it was supposed to be all about than the killing that is at its core…But evil among our elites is more often a matter of willful ignorance and passivity—of blindness—than of any deliberate cruelty. And Kubrick emphasizes that culture and erudition have nothing to do with goodness or depth of character."

Kreider:

"Critical disappointment with Eyes Wide Shut was almost unanimous, and the complaint was always the same: not sexy. The national reviewers sounded like a bunch of middle-school kids who'd snuck in to see it and slunk out three hours later feeling horny, frustrated, and ripped off…Once again, critics could only see what wasn’t there. The backlash against the film is now generally blamed on its cynical, miscalculated ad campaign. But why anyone who'd seen Kubrick's previous films believed the hype and actually expected it to be what Entertainment Weekly breathlessly anticipated as ‘the sexiest movie ever," is still not clear.’…The main title then appears like a rebuke, telling us that we're not really seeing what we're staring at… The intensely staged vacuity of the Harford's inner lives should tell us to look elsewhere for the film's real focus. One place to look is not at them, but around them, at the places where they live and the things they own…The Harford’s standard of living raises questions about their money, and where it comes from.” Our modes of seeing also raise questions about suffering and corruption and where it comes from and what's really behind it, like "the slap heard around the world."

Like Eyes Wide Shut, Netflix’s utterly terrifying and haunting two-part documentary, Jimmy Savile: A British Horror Story (2022) reveals a secret in order to keep an even bigger secret. And this has been the pattern for the last few years with the exposés of the streaming-era. The more I understand how the world really works, and the awful extent to which that system dominates everything now, and maybe always has—my naivete was never cultural, moral, or social, it was political and religious—the more difficult it is to go on writing the way I did. To go on writing at all. I am reading things the wrong way--or the wrong things in the right way. We all are, even the best of us, with the best intentions. More precisely, like the Savile documentary, I am interrogating the wrong secret, albeit for the right reasons, while the bigger secret, the one almost no one knows or talks about, and that no one can stop even when they do talk about it. Is there anyone not involved in these terrible things? Is this what really drives the story? Maybe even the whole story? The story for which “art” is also a cover. For which culture (and now the culture wars) is a cover. Is a cultural critic simply a patsy vocation for an assassin world order that merely pretends to make cultural objects in order to possess and ensnare a civilization? Even the patsy critics no longer have any use in this new era, hence the erosion of their personal and collective caliber and integrity. Talent was always the miracle, not Art. Art was a program. Even a psyop, certainly since Warhol. The new world order no longer needs to pretend that critics and artists serve an illuminating social function by giving them a powerful interpretative/imaginative voice. In other words, I am critiquing the wrong things; things that are merely facades or effects of something that has nothing whatsoever to do with art, culture, justice, or social events, and even if they do, they don't make a difference. They don't eliminate evil. Given this, given what I now know, what I have always intuitively felt, sensed, and feared, but I was trained to resist, address, and express intellectually—which is to say secularly, with a materialist verdict; with a disbelief in the occult underpinnings of cultural happenings and icons—how can I finish my books? How can I continue to write? A critic today, no matter how good, honest, or ethical, is still a patsy because they are exposing the wrong truth. They are exposing one truth to hide another.

Kreider states that masks (the ongoing subject of all my work) are inverted in Kubrick’s Eyes Wide Shut: “Note that when Ziegler first sees Bill enter the ceremonial hall [of the Satanic orgy], even though they are both masked, he gives him a knowing nod. He recognizes him. Here the guests at Ziegler's party are unmasked for what they really are.” In other words, the masked orgy is an unmasking, the true meet and greet; the Christmas Ball is a disguise. The costume masks are the real faces of the people behind them. Bill Blakemore echoes Kreider’s conclusion in his 1987 essay on The Shining, “The Family of Man,” writing:

”That's why Kubrick made a movie in which the American audience sees signs of Indians in almost every frame, yet never really sees what the movie's about. The film's very relationship to its audience is thus part of the mirror that this movie full of mirrors holds up to the nature of its audience…Kubrick is examining in this movie not only the duplicity of individuals, but of whole societies that manage to commit atrocities and then carry on as though nothing were wrong. Though he has made here a movie about the arrival of Old-World evils in America, he is exploring most specifically an old question: Why do humans constantly perpetuate such ‘inhumanity’ against humans? That family is the family of man.”

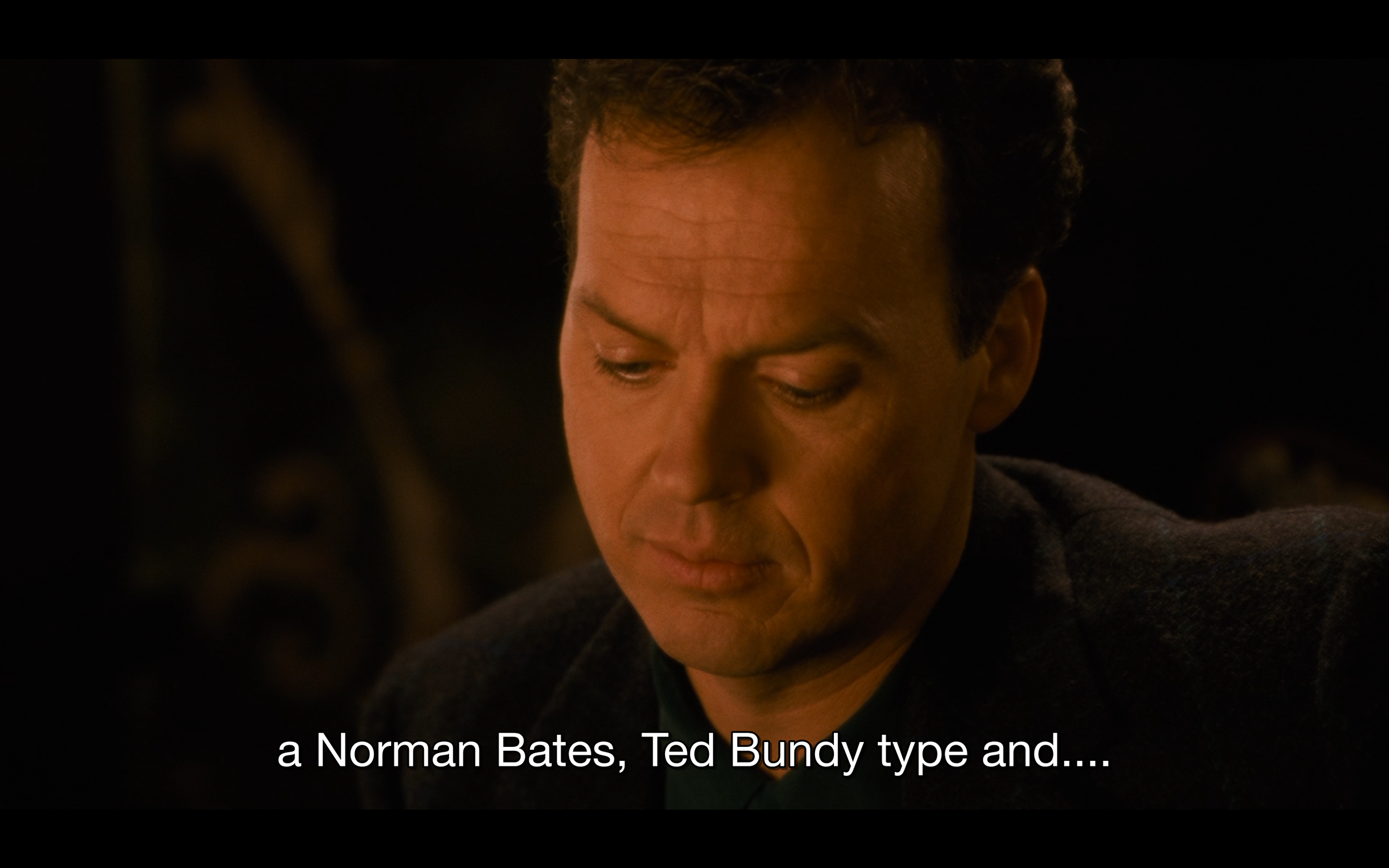

Victor Ziegler’s lavish New York City mansion, where Eyes Wide Shut’s opening Christmas Ball is held, is reminiscent of the haute-ghouls at the haunted Overlook Hotel. The remote mansion where Eyes Wide Shut’s orgy scenes were filmed is the Mentmore Towers in Somerset, England, built for the Rothschild family in the 1850s. The estate is the site of a Rothschild-hosted 1972 masquerade ball. The elites in attendance at these parties—a mix of ghosts, sirens, and monsters—are not what they seem. Nothing is real at the Overlook, nothing is real at Ziegler’s. Everything is orchestrated and staged. Despite what many critics have argued, Eyes Wide Shut is not a dream. It is pretending to be a dream. The oneiric or conspiratorial is simply a cover for a complex superstructure of machination. Even the film’s covert dialogue is constructed this way: Nick Nightingale tells Bill: “Everyone is always costumed and masked.” The owner of the Rainbow costume rental shop covertly offers his daughter’s underage body to Bill this way: “If the good doctor himself should ever want anything again, anything at all, it needn’t be a costume.” Nebulous billionaire Victor Ziegler tells Bill: “Suppose I told you that everything that happened to you there, the threats, the girl’s warnings, the last-minute interventions; supposed I said that all of that, was…staged. That it was a kind of charade. That it was fake.” At the end of the film, Alice tells Bill: “Maybe I think we should be grateful that we’ve managed to survive through all of our adventures, whether they were real or only a dream.” In response Bill tells Alice: “And no dream is ever just a dream.” Each thing (person, place, event) in Eyes Wide Shut is a secret code for something else. The film will not reveal what it is really about. It will not tell us who Victor Ziegler really is. Cryptocracy is shrouded inside the film’s Christmas mise en scene. Tom Cruise’s acting career is a cover for his Scientology agenda. Nicole Kidman’s marriage to Cruise was a cover for Cruise’s rumored homosexuality. Bill’s alchemical quest to betray his wife is sparked by his fear of being betrayed. Kubrick’s cinematic fascination with Cruise and Kidman’s real-life Hollywood marriage is a diegetic indiscretion that undermines the sanctity of marriage. And on and on it goes. For Kubrick, to scrutinize and puncture these domestic and social worlds is to simultaneously tarnish and expose them as fraudulent, corrupt, and miserable. Eyes Wide Shut itself is a mask for what it is showing us. And because it operates as simply a fiction, we can never call what we discover in it true.

I am reminded of the intimate dance scene between Selina Kyle and Bruce Wayne in Tim Burton’s Batman Returns (1992), which I revisited in the summer of 2022. When the two-faced paramours encounter each other at Max Schreck’s masonic charity ball without their vigilante masks, they realize that they are the nocturnal rivals Catwoman and Batman, a rivalry predicated on the war between the sexes. Each deceiving the other, the realization of their secret identities makes them sense the imminence of their conceptual deaths as avenging alter-personas and nemeses, seeing each other for who they really are and for how they really feel (Selina tells Alfred Pennyworth that Bruce Wayne “makes me feel the way I hope I really am.”). But which is their double, the interspecies superheroes they moonlight as or their fragile human self? Because they cannot ultimately risk or face the egoic death of their covers, nor accept the truth of what they have uncovered about themselves or each other, Bruce and Selina once again take shelter in their masks and alters. Like the masked sex party in Eyes Wide Shut, in which interloper Bill Harford is ordered to remove his mask by the elite cabal, Batman Returns has everyone but Selina and Bruce masked at Schreck’s ball. Yet their unveiling only deepens their existential estrangement, disassociation, and need for cover. Neither feels freed by knowing who the other is and neither knows how to abandon their alter ego. Their human faces tell us who they cannot and do not know how be. In Batman Forever (1995), Batman, who is battling with the demon of repressed memories—the death of his parents as a little boy—tells the psychologist, Dr. Chase Meridian (who like Louis Lane with Superman, is in love with Bruce Wayne’s alter-ego, Batman, “You want to know who I am? I guess we’re all two people. One in daylight and one we keep in shadow.”

The 17th century Venetian masquerade masks (Baúta) worn at Eyes Wide Shut’s sex orgy are almost early prototypes of transhumanist morphology and mind control, which perverts and dissolves the line between human and machine, face and mask, core self and altered self. In an October 2022 interview with Megyn Kelley, journalist Andrew Sullivan made the following remark about the programming of faces in the post-digital era: “So many people now, they’re developing faces that really aren’t faces at all, they’re masks. And they’ve become permanently fixed on their face.” Sullivan is referring to the de-facing plastic surgeries of transhuman celebrities like Madonna and Kim Kardashian, who foist their bizarre cyber-masks and facial alterations upon the public as beauty ideals and human norms via the influence economy and Big Tech AI platforms while insisting their mask-systems are real. If biology no longer exists or matters, and reality has no basis in truth, the proclamation, “I’m natural” is both an easy and meaningless claim to make given the ambiguity and falsity of the claim. Doublethink insists that all truths are true even when they contradict or negate one another. But lest we forget, despite how rare its become: a truthful face is not the same thing as a real face. One reveals what one is, the other covers, distorts, and disguises it. Given that the main tenant of most New Ageism is self-obsession, the biomedical quest for the “perfect” face is a prime example of this counterfeit gospel of doublethink. As George Orwell writes in 1984: “That was the ultimate subtlety: consciously to induce unconsciousness, and then, once again, to become unconscious of the act of hypnosis you had just performed."

It is Bill’s party mask, not Bill, that sleeps beside Alice in bed at the end of Eyes Wide Shut. For, even before Bill puts on his rental costume, his face begins to alchemize with the topographical symbols of the shadow world he has fallen into. Later Bill’s mask on his bed pillow morphs into a kind of Freudian Janus. Janus, the Roman god of beginnings and endings, and who presided over passages, doors, gates, and endings, was usually depicted as having two faces that faced in opposite directions (Francis Ford Coppola’s promotional poster for Dracula (1992) takes a similar approach to its monster). One face is for the past, one face is for the future. A literal two-face. A double of a double. Yet, in Eyes Wide Shut, even Bill’s masks do not match. The mask he wears—and supposedly “lost”—at the sex orgy is not the mask that later appears on his bed. They are different colors. So how can we know for sure it was Bill at the party? Once he puts on the mask, it is no longer clear who is really behind it.

There is perhaps no better popular example of the power of the modern mask than the 1994 American comedy, The Mask, which came out five years before Eyes Wide Shut. In it, hapless pushover, Stanley Ipkiss (Jim Carrey in his prime), is emasculated on a daily basis by the cruel world around him. The Mask is a Jekyll and Hyde comedic reboot, reminiscent of Jerry Lewis’ charismatic contribution to the timeless fable, The Nutty Professor (1963).

The ancient wooden mask Stanley finds in Edge City river one night is a “4th or 5th century Scandinavian, possibly a representation of one of the Norse night gods, maybe Lokki.” A banished god of mischief. Like Bill Harford, the spell of Stanley’s alter-ego is nocturnally activated. When he consults with the popular anthropologist, Dr. Neuman, the author of The Masks We Wear, Neuman reminds Stanley that his book is about the mythology of masks. Masks, he tells him, are simply metaphors, “a metaphor, not to be taken literally.” To treat the power of masks literally is to suffer from “delusion.” Stanley tries to prove to Dr. Neuman that the magical spell of the immortal god, Lokki, is real, but when he puts on the mask in front of Dr. Neuman nothing happens. He simply appears to be jerking his body around violently for no reason.

Do these 90s films live in a world of metaphor or do they live in a world of delusion? Is Stanley’s green-faced alter real or simply in his head? Is the mask external or internal? Stanley explains that the mask is who wears it. It is also daytime when he visits Neuman’s office, and Lokki, we’re told, only comes out at night. It may be that the mask is simply the result of the power of suggestion. A placebo effect. It gives Stanley, a pathologically “nice guy,” the confidence he lacks to express his “inner most desires,”which are not nice. With the mask on, Stanley “can do anything, be anything.” The green mask becomes the green face. “That man is The Mask.” “You’re the guy with the face.” But night itself is a mask. A double for day. A vampiric cover for the nice guy. One of those metaphorical or diurnal screens Dr. Neuman mentions. Who we are at night is not always who we are during the day. Like Stanley Kubrick’s recreation of New York City’s Greenwich Village (why not just film the City for real?), The Mask’s Edge City is also a made-up place, a present-day oneiric mask for the filmic past. In the movie, the mid-90s splits its time with the 1940s, a retro-present world full of cotton clubs, Copacabanas, cartoons, slapstick, Americana, old movies. Stanley wants to confront Tina (Cameron Diaz), his sultry love interest, but doesn’t know whether he should do it as himself, or “the mask.” Which one will she prefer? Which guy does she like more? These questions pertain to the internal masks we wear, the ones others can’t see. But what about the literal mask? Bruce and Selina go to the ball as themselves but don’t feel connected to who they are without their covers, so are their real faces real? They do not feel more honest without their masks. Maybe they have no true faces, no one seems to in the 90s. Dr. Neuman’s advice to Stanley is to break the binary, to integrate and reconcile the internal and external mask: “Go as yourself and as the mask because they are both one and the same beautiful person.” “The Mask” man himself is a pastiche; a mashup of alters: people, costumes, accents, movie dialogue, genres, and vocal impressions.

*

Despite his great talent and powerful eye, which meticulously shed light (perhaps “light” is the wrong word because Kubrick never offered any light), on so many different kinds of evil (was this his specialty?) for half a century, Kubrick may not have been an especially good man, and himself brought suffering onto others in the name of his art, which, like all mainstream fare, no matter how interesting, must always cover up what it exposes. Great art can be a cover, a double, or atonement for the otherwise bad behavior of the artist. In today’s world, we have come to see this as a reason to punish or cancel both the art and the artist (though there is no consistency in how or when this happens, apart from political agenda) instead of regarding the artist’s productive sublimation as the greater gift, the greater deed; a silver lining in the continual problem of what it means to be human, we fault art for what it hides (the sins of the artist) rather than for what it exposes (humanity). All art is made by a double, whether thematically or procedurally because its very praxis/creation is predicated on two modes of being—art and artist. At its best, art is a useful and productive tool of sublimation because it gives us in art what the artist cannot give in life. Great art can purge and redeem what is corrupt, flawed, and morally inadequate in us. Good art reveals something allegorically instructive about what is bad in us, which can be useful for others. It can reveal what happens to us—to all of us—when we are bad. But art that exposes evil is also an advertisement for it, as with the Victorian-era novels about the depraved male double.

Did Kubrick care about the existence of the evils he exposed or was he just very good at exploiting them visually? Was his art a cover? Did it unveil by veiling? All art is an exercise in doubling and splitting.

Kreider writes that “In Eyes wide Shut, we see [masks] not only at the orgy but throughout the film, always as harbingers of death.” If we take a conspiratorial view of Hollywood as diablerie, and cartel, movies hide something (bad) by showing us something (good). Likewise, Hollywood purports to give us something by taking something more important away. Even Kubrick’s shooting style famously took the form of subterfuge. He shot in secret, on his own terms, with his own very small crews. He kept a very tight lid on his film productions with the press. The Eyes Wide Shut shoot took 400 days, and Kubrick spent 30 years reworking the script. This was seen as the mark of a true auteur in control of his art. Eyes Wide Shut’s, concludes Kreider, “open-ended narrative forces us to ask ourselves what we’re really seeing; is Eyes Wide Shut a movie about marriage, sex, and jealousy, or about money, whores, and murder? Before you make up your own mind, consider this: has there ever been a Stanley Kubrick film in which someone didn’t get killed?”

Right. And has there ever been a good celebrity, politician, or powerful rich person who wasn’t at some point exposed as—for—something terrible? (even if that terrible thing was not really being the public persona they had adopted). Or even worse, not exposed for something terrible.

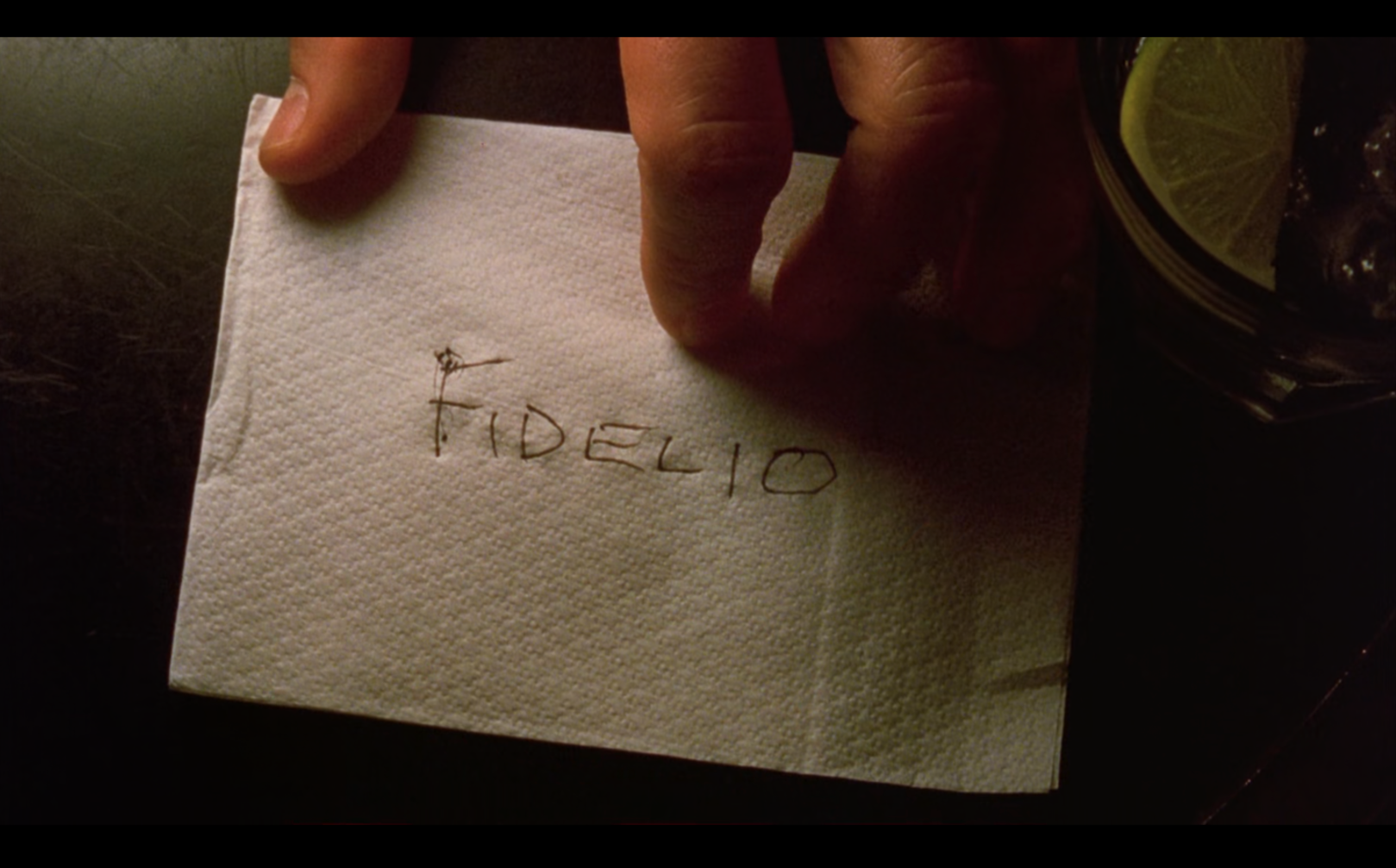

As Eyes Wide Shut shows us, the password for fidelity is betrayal.