12:18:23

Chiaroscuro. Hellraiser. Snowshaker.

Gary Goldman, The Firm 1988.

I have never understood acting (Gary Oldman: “There’s such bullocks talked about acting.”), that’s why I write about it so much. The book I’m writing now, Time Tells, vol 2., is dedicated to acting’s strange phenomenologies/politics/horror/glamor. Acting is not normal. But of all the not-normal people to do this incredibly not-normal thing in our incredibly not-normal world, there was no one better at doing it during the 1980s-1990s than Gary Oldman—a loner-actor—besides Jeff Bridges. I am excluding actors from other cultures/countries here. I’m talking specifically about actors that came to us through Hollywood’s occultic portal.

The high broad cheekbones of Oldman’s young (late 80s, early 90s) face really get to me. See State of Grace, see Rosencrantz & Guildenstern Are Dead, see Dracula. I love his face—and the pompadour hair—most in Criminal Law (1988), which, hard to believe, came out the same year as Alan Clarke’s The Firm. No wondrous interior-esque expressive faces like this exist today. His face is alive. Oldman is more creature than human. I’ve always been convinced that onscreen performances are just whatever actors happen to be experiencing in their real lives at the time they play a role. As bad as this may sound, I prefer Oldman’s face before he quit drinking “two bottles of vodka a day.” Oldman drank through the entire shoot of State of Grace, like his character Jackie, who drinks and drinks. After Oldman stopped drinking, he became very thin, and his face sank and lost its form. Those big wide cheekbones flattened.

I’ve always been very curious about alcoholics. I write about the addiction of alcohol; the broken promises of the addict—what kind of people drink versus what kind of people do drugs—in Famous Tombs: Love in the 90s, from my 2019 book Picture Cycle, citing Avital Ronell via Baudelaire: “At one point Baudelaire seems to ask: whom are you preserving in alcohol? This logic called for a resurrectionist memory, the supreme lucidity of intoxication.” The answer for Oldman was his father, who abandoned him and his mother when he was a child. His father, he says, was also an alcoholic. “I remember the promises,” says Oldman. We all do. Baudelaire is right, I am never more myself or closer to the things I feel than when I drink. Oldman’s early screen characters were always inflamed. Impassioned. Maybe I like that right kind of anger in men. Anger that is channeled and directed in the right ways, at the right times. Maybe it’s the refusal to be fucked with, or misdirected (in Oldman’s case, this was literal. Good actors hate to be mis-directed), as we see in the BBC profile linked above, where Oldman famously retaliates against Francis Ford Coppola in the behind-the-scenes of Dracula (1992). Rage exists and it has to go somewhere. Rage exists and it must be used when we are being mistreated. Anne Carson: “Grief and rage--you need to contain that, to put a frame around it, where it can play itself out without you or your kin having to die. There is a theory that watching unbearable stories about other people lost in grief and rage is good for you--may cleanse you of your darkness. Do you want to go down to the pits of yourself all alone? Not much. What if an actor could do it for you? Isn't that why they are called actors? They act for you. You sacrifice them to action. And this sacrifice is a mode of deepest intimacy of you with your own life. Within it you watch [yourself] act out the present or possible organization of your nature. You can be aware of your own awareness of this nature as you never are at the moment of experience. The actor, by reiterating you, sacrifices a moment of his own life in order to give you a story of yours.” (Grief Lessons: Four Plays by Euripides). Rage, writes Carson, is always grief, so Oldman drank, imitating his father, acting like his father, and somehow, he says, he could still act with no problems, until The Scarlet Letter (1995), when he couldn’t remember the words. It’s hard to imagine. By which I mean, after two bottles of vodka, how did he EVER remember his lines?? Carson says there is a correlation, between acting and rage. Between rage and intimacy. How can you know yourself and what you believe in—what you truly want—if you never get angry when it is lost, taken away, or trampled on. If you do not take action to get it. To earn it. You can and should also fight for others, not just yourself. Principles are no small thing in this world, but having them also requires anger. Principles are meant to be demonstrated. Lived. Felt. Acted on. Honored. What is the correlation between addiction and acting? Between being yourself and being someone else all the time? How does acting split us and require us to remain split? Possessed, broken, programmed. That’s what I am trying to figure out.

“I used to torture myself.” (2019 talk)

Oldman told Luc Besson to shoot his famous pill popping scene in Leon/The Professional (1994) from above. He described it as a werewolf transformation scene. Vampires and werewolves are a version of the addict. An addict, as I write in Famous Tombs, also changes into someone—something—else. Everyone online always wants to know what secret "pill" Oldman’s psycho-cop takes to make him turn into that monster. But what kind of monster is it? It’s partially the not-knowing what drug it is that makes it so terrifying. How can you understand what he is becoming if you don’t know what he is taking to become it? I have scrolled through the online forums, read the theories. Some claim Librium. Others: “It seems like a made up drug.” This mysterious single pill lives in a pill box, which makes it extra special, extra mysterious, extra dangerous. Oldman’s character crushes the pill in his teeth, then convulses. Can you imagine being that intense in your performances and not remembering them? Jack Nicholson said he was possessed while playing Jack Torrance. Actors are so bizarre. But we also don't have actors like Oldman anymore because we don’t have people like that. Or faces, or bodies, or voices. Or movies.

In one interview from the 1990s, I can’t remember which (I read it years ago), Oldman said he used to check into the most expensive hotels just to binge drink for days alone. telling the concierge not to disturb him while he was there. Holing up to die. Using his money to die. It's a gross, dark image. Oldman was reportedly very difficult on sets—not just the Coppola-Dracula set, but the Leon shoot as well. Difficult actors, that should be another essay. But why are they difficult? What is their problem? As viewers who fixate on movies and performances, it is strange to think of actors not being able to remember film shoots because of their addictions. James Spader has always said he does not remember making Pretty in Pink, not because he was fucked up, but because he looked down on the film. Andrew McCarthy, who was also in Pretty in Pink, says he can’t remember many of the films he made because of his drinking. Matthew Perry, a lifelong drug addict who recently died, said he couldn’t remember three seasons of Friends because he was high on pills and booze the entire time. His hangovers while shooting the show were profound and overwhelming. And yet, the show ran like a well-oiled machine and made the cast multi-millionaires. How does one act in such a debilitated state or in such a state of debilitation—a state that precedes the addiction—the reason and prerequisite for acting? Living a double life. Living many lives. Living bifurcated lives. Living fake lives. Living corrupt lives. Not being oneself, being others by trade. By training. By programming. Can you have acting without addiction? You certainly cannot an honest addict. Can you have an actor without splitting? If we were normal, at peace—integrated—I don’t think we would act. Not on film anyway. Or we would have movies without the idoltry. Without the movie star worship. Without the endless lying. Without the toxic celebrity culture that permeates everything. Something is so off. And it never ends well. As Celia Farber put it today on her Substack post on the Russian ballet dancer Sergei Polunin and Monarch programming, which I believe all stars undergo: “Fame Is Filth. Fame is a consequence, a burden. Not a good thing. Not a thing to envy. Nobody should worship anybody, under any circumstances. It’s disgusting, actually. And it’s used by the illuminati, to great effect.” Robert Bresson famously didn’t use actors, didn’t believe in them, disavowed actors, or so he thought—that’s another essay in Time Tells, vol 2—Bresson and actors. I think Bresson was naive to think he could get movies without actors. I don’t think films as we know them can exist without actors. It’s too late to undo that. Hollywood is programmed into our psyches. But that’s ending now, little by little. In Oldman’s case, sobriety has made him a more boring, more conventional actor.

Lastly, a side note: like me, Oldman is a triple Aries (Sun, Moon, Mercury), with a Scorpio north node (his in the 5th house, mine in the 3rd). His Venus and Mars are in the 8th house. We’re both Scorpionic Aries, or as one astrologer once put it about me, “You’re like a closet Scorpio.” Mars (the Divine Masculine) is action, the Roman god of war. The son of Jupiter and Juno, the wife who never got what she wanted and deserved from her cheating husband. Oldman was also a cheating husband. Like his father, he left his first wife, Lesley Manville (who plays Oldman’s wife in The Firm. I think that is when they met) and infant boy for a 19 year old Uma Thurman, who left Oldman within a year because he was a drunk and a terrible husband). In astrology, Juno is what you need in love, Venus (the Divine Feminine) is what you desire. We usually know what we desire (and want is also something different), but not what we need. Mars is also, plain and simple, a warrior for what is rightfully ours.

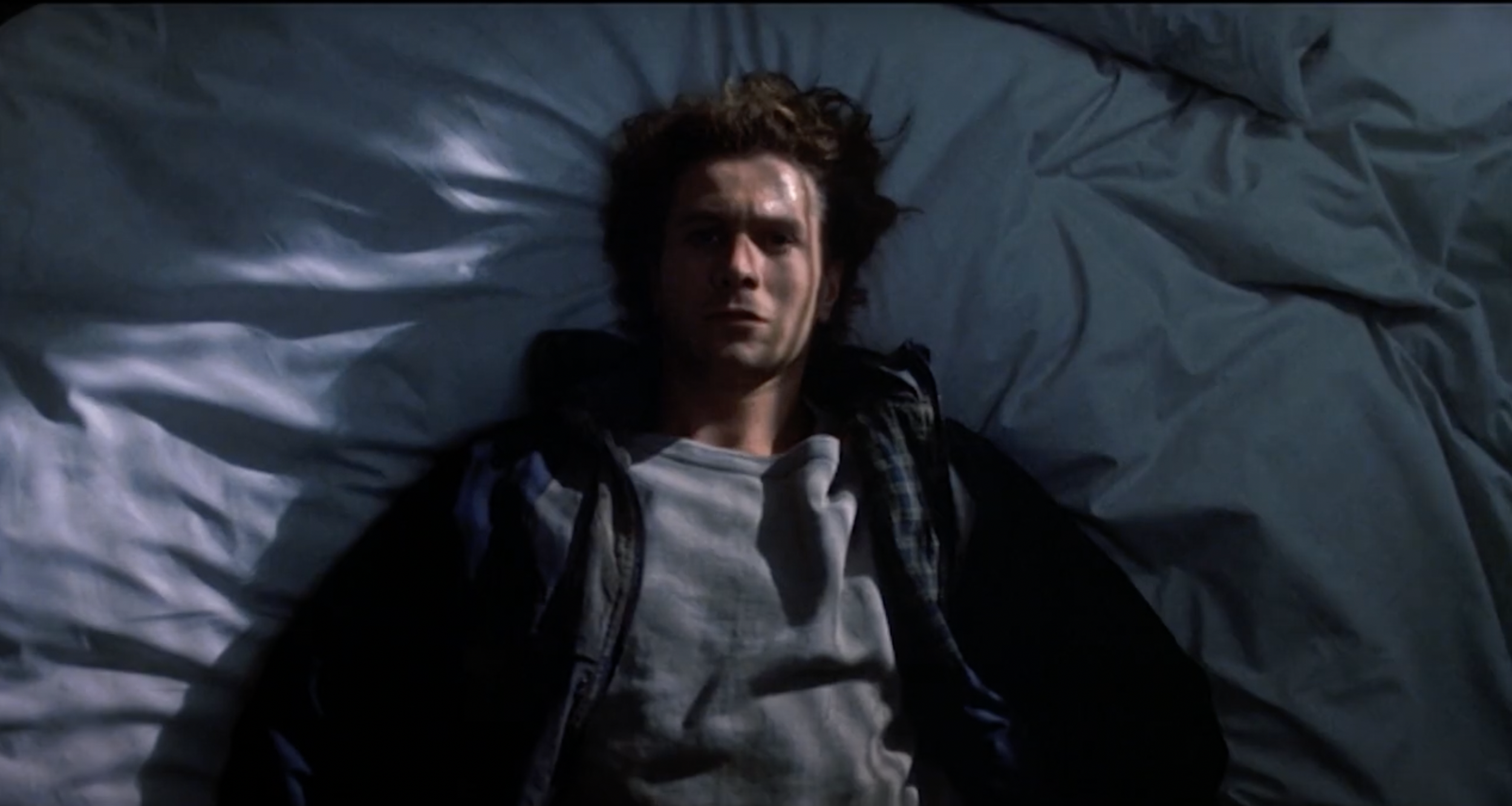

These two scenes—above and below—are my favorite Gary Oldman images, from Criminal Law (in this Criminal Law interview, 5 years before Leon, Oldman is, strangely, in Norman Stansfield attire) and State of Grace. He’s as lush as those bedsheets. And in the second screenshot, him looking out the window, cigarette in mouth, in the empty Soho loft, which overlooks Mercer Street in New York City, right over Fanelli’s cafe, where I spent my childhood with my parents and their friends.